Guido's Rhombus

In the early fall of 2003, just prior to his death in February 2004, Guido Molinari urged me to consider making a series of works ‘on the point’—I promised him I would.

§

I come from a large family and time alone with mom was earned. It was the 1960s and I made a number of visits to the National Gallery of Canada with her, and our visits were something we did apart from my brothers and sisters. We would go to the pancake house first, and from there to the gallery, which was then located on Slater Street, facing Elgin. There was a group of stuffed life size camels by American artist Nancy Graves in the lobby of the Gallery; I loved those camels, so when it was my turn to do something just with mom, we went to see the camels and the paintings.

On one of these visits to the Gallery, we came to a room that had a stanchion across the entrance. There were people working inside and pictures leaning against walls, opened crates and packaging was strewn about the gallery floor. I asked mother “why can’t we go into that room?” She explained, “the men are working, that they are hanging those paintings,” and (pointing) “that man, there, is the artist.” What a revelation for me; what did she mean the artist? An actual living artist! I thought artists came from Italy or France and that they had all died hundreds of years ago—was it possible, then, that grown ups could make pictures throughout their lives? My idea about men was that they left each day, and sold buildings or land for a living. I had never imagined that you could keep making pictures, which was my favourite thing to do, for the rest of your life. My mother seems to remember that the artist in that room was Guido Molinari.

§

While a student at York University in the early 1980s, I worked for a few art dealers as a way to pay for the drawings and paintings that I had started to acquire. One of the dealers was Fela Grunwald, who represented Molinari in the early 1980s, and had an exhibition of his “quantifiers”. I remember the show clearly and while in the gallery I made careful measurements of one of Guido’s pieces. Later, back at the studios at York, I made a copy for myself. It wasn’t very good, but it was a constant reminder of how profoundly beautiful that exhibition at the Grunwald Gallery had been.

Years later, in the early 1990s, I was represented by Wynick Tuck Gallery in Toronto, and as it happened, so was Guido Molinari. He had a show of large works, squares on the point, and was due to be in Toronto for an evening at the Gallery. I had recently acquired a small blue “quantifier” by Molinari, from the Gallery, and was anxious to meet a genuine hero. It was a fantastic evening and afterward I offered to give him a drive to the airport, so he could catch his flight back home to Montreal. We talked non-stop, and eventually I asked him about the show at Grunwald Gallery, the quantifiers he’d shown then, and then confessed to the copy I had attempted while at school. I added, however, that now that I owned the real thing and had covered up that copy — after all, I could use the canvas and the stretcher again. He laughed, actually laughed, and then confessed to making his own copy of a Mondrian a number of years ago and then added, “but now I own a Mondrian, which you must come and see.” I asked if he had covered up the copy he had made; I suppose I was looking for more things we might have in common. “No” he assured me, it was “far too good.”

After this first meeting I was able to visit Guido in his studio a number of times and was lucky enough to have him visit me in mine. He showed me the work in his collection and I showed him the work in mine.

I acquired a second “quantifier” in 2001; this one was much larger than my first and red. It lives with me in my studio and I look at it with tremendous affection each and every day. In the early fall of 2003 I visited Guido for the last time. We talked a lot about painting, about abstraction and representation. He showed me some of his techniques, and urged me again to consider the challenge of working on the “point.” I promised I would and have attempted it a few times; twice with cloud works and twice again with flower pictures. Unfortunately I never had the chance to show these attempts to him, but somehow I knew that these were not exactly what we’d discussed.

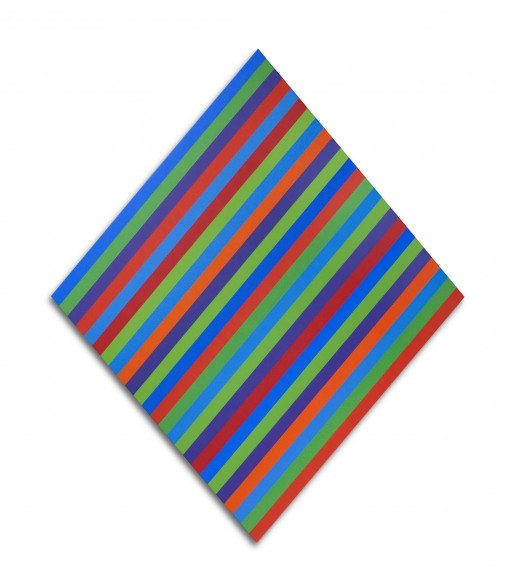

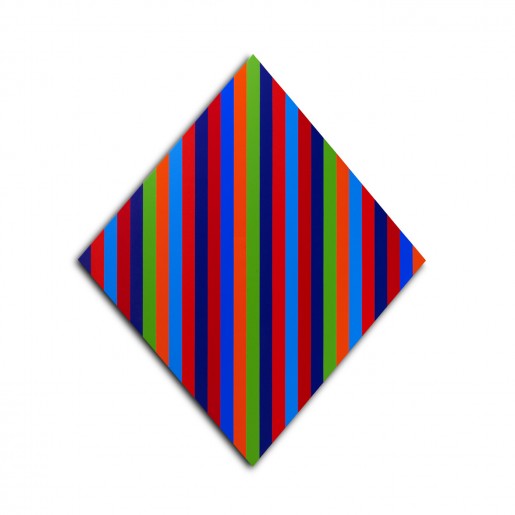

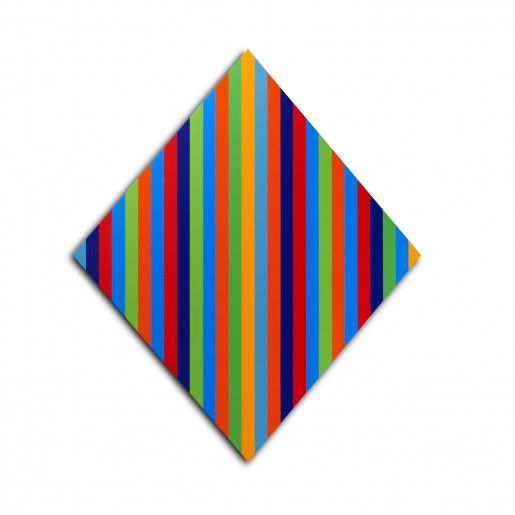

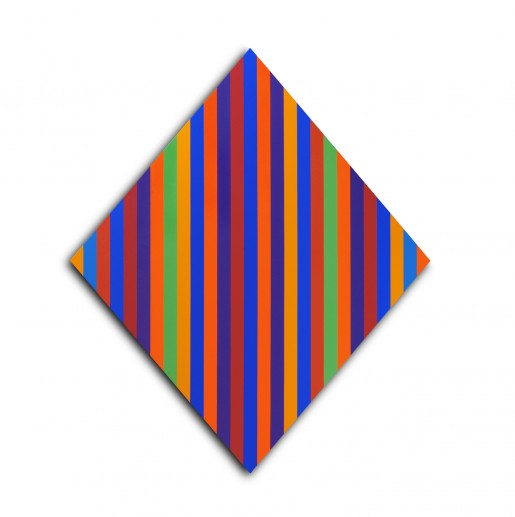

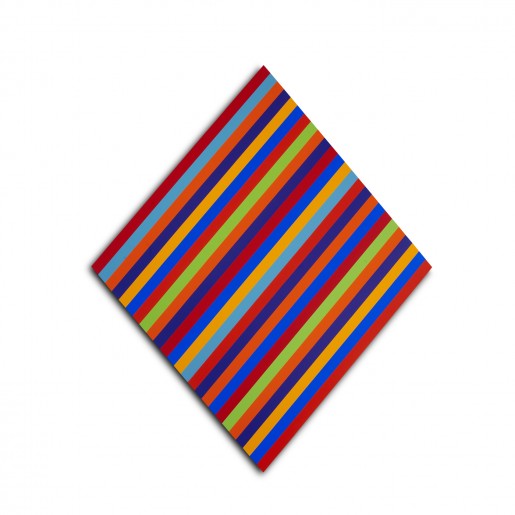

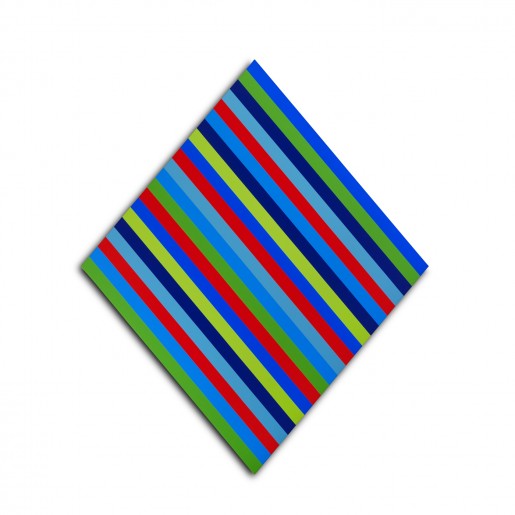

So, I’ve been thinking about the “point” for almost 6 years now and I decided this past fall to undertake the pieces from this series. Unlike earlier attempts, these are not rotated squares. Rather, these are rhombus canvases; an equal sided parallelogram featuring 2 equal and opposite oblique angles and 2 equal and opposite acute angles. I have decided to focus on Molinari’s mutations from the 1960s as an initial source; from that first childhood encounter with his magic, a dotted line to that world of wonder back then, and forward to a promise made to giant who gave me some of his time, when he didn’t have to. This series of rhombus abstractions are my attempt at the fulfillment of that promise.

James Lahey

December 2008